Western Australia is the only Australian state whose carbon emissions are rising. The gas industry is to blame.

Eyrie is a novel by the poet laureate of Australia’s coastline, Tim Winton. In it, former environmental activist Tom Keely awakes hungover in a high rise apartment. Tired and disorientated, he peers out over Fremantle, nestled on the shores of the Indian Ocean.

The port city is, Winton writes: “(The) gateway to the booming state of Western Australia. Which was, you could say, like Texas. Only it was big. Not to mention thin skinned. And rich beyond dreaming. The greatest iron ore deposit in the world. The nation’s quarry, China’s swaggering enabler.”

It’s an apt and cutting description. But through Keely’s eyes, Winton undersells the mining credentials of Western Australia. It isn’t just the nation’s quarry – it’s the world’s. WA alone, forgetting the rest of Australia, generates more iron ore than any other country on earth. With these staggering numbers it’s easy to forget – or perhaps not even consider – that the state has another industrial relationship, one that also marks it a world leader in extraction.

And that’s with natural gas.

Australia was, up till recently, the world’s largest exporter of liquefied natural gas (LNG), gas that has been tapped and cooled to a liquefied form in order to transport it more easily. Of this, more than half originates from WA. Gas is the state’s second most valuable commodity after iron ore.

Now, this relationship appears set to supercharge. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has sounded alarm bells around European energy security, as the majority of oil and gas used on the continent comes from Russia. With sanctions hitting Russian suppliers, Australia has been flagged as the key player to prop up global demand. What this means in practice is that the price of LNG has exploded, and the state and federal governments are on a unity ticket to exploit it, with multiple, mega projects at play now across WA’s vast landmass.

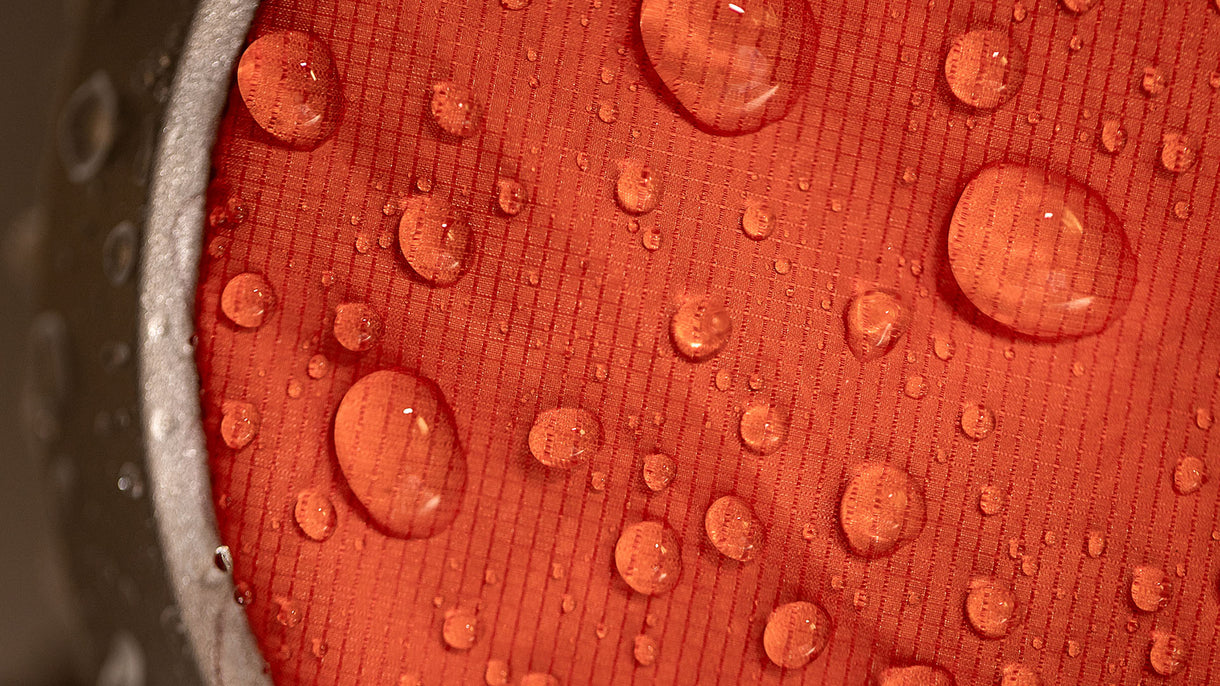

As the offshore gas industry encroaches as far south as the Ningaloo Reef World Heritage area – and now with the Kimberley being opened up to fracking – gas extraction in the west is being supercharged at a time when Australia is being asked to commit more heavily to climate action. Photo Chris Gurney

As the offshore gas industry encroaches as far south as the Ningaloo Reef World Heritage area – and now with the Kimberley being opened up to fracking – gas extraction in the west is being supercharged at a time when Australia is being asked to commit more heavily to climate action. Photo Chris Gurney

Leading the charge is Woodside’s Scarborough hub in the Pilbara, which recent studies say would release 1.6 billion tonnes of greenhouse gas across its lifetime – the equivalent of 15 coal-fired power plants. Similar concerns exist around fracking. An unconventional method of extraction, fracking uses a cocktail of water and chemicals to release gas by fracturing rock seams deep underground. Community concerns for the health of people and the environment saw the state government actually ban the process across over 90 per cent of WA in 2018.

Not so however in the Midwest and Kimberley. These areas hold the state’s largest reserves of onshore gas and mining companies are already canvassing potential sites despite studies forewarning that largescale fracking in the Kimberley could blow Australia’s carbon budget. Applications have even being put forward to search for oil and gas within kilometres of the Rowley Shoals Marine Park, off the coast of Broome, one of the most pristine reef systems in the world.

Before this expansion begins, however, WA’s track record with gas extraction has certain questionable outcomes that need to be addressed. Currently, WA is an outlier. The National Greenhouse Accounts show that between 2005 and 2019, every Australian state actually reduced their carbon emissions – every state, that is, except WA, whose emissions increased by 21 percent during that time. This is especially significant because, given WA’s fixation with LNG, the west coast may prove to be the deciding factor as to whether Australia has any chance of decarbonising into the future.

During the 2021 United Nations climate change conference – COP26, reported on here – countries were urged to write 2030 emissions targets into law. In response, Australia pledged, without actually legislating, to reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050. Western Australian Premier Mark McGowan has said that his state will follow the federal government’s lead, but at the same time has also backed in the gas industry. McGowan declared late last year that expanding the Scarborough project alone would result in thousands of new jobs and local economic growth.

However, this constant political refrain of employment and revenue may have to be approached with a degree of caution when it comes to gas. A recent report from The Australia Institute found that, even with WA forming the backbone of Australia’s LNG exports, oil and gas extraction currently employs less than 1 percent of the state’s total workforce.

Similarly, revenue wise, there doesn’t seem to be a lot to show for what is WA’s second most valuable commodity. While iron ore generates almost $8 billion a year to the local economy, gas provides just $425 million. To put this in perspective, this is less than half of the revenue that car registrations make to the state treasury.

And then there’s the price of gas. In 2020, Australia was found by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission to have far higher gas prices than its neighbours in the region, as most of the LNG that is produced here is shipped straight off to Asia. Despite this, federal energy minister Angus Taylor has warned that Australia faces an energy crisis like in Europe unless more is done to boost the country’s gas supply. You would be forgiven for scratching your head on this point. How can the nation that has some of the largest gas reserves on the planet, produces more LNG than anywhere else and sells it cheap to its northern neighbours be at risk of running out of it?

Western Australia is the only Australian state where carbon emissions have been increasing, and that's without including the emissions produced by the West's LNG exports. Photo Chris Gurney

Western Australia is the only Australian state where carbon emissions have been increasing, and that's without including the emissions produced by the West's LNG exports. Photo Chris Gurney

Now, Prelude – the largest vessel in the world – has quietly made its way back to Australia and has moored off the coast of Broome. Mineral extraction on its grandest scale, Prelude is a floating 488 metre platform, capable of extracting and producing LNG offshore. And yet, despite its status and size, Prelude has been plagued by safety issues over the past two years. A gas leak in 2020 saw the vessel shut down production for almost twelve months. Then, in 2021, electrical faults led to the facility catching fire with workers evacuated. A safety submission must now be accepted by the government before operations continue.

So, with all this talk of expansion, the question begs to be asked… if the gas coming through WA is not being sold on the domestic market; contributes less to the local economy each year than car registrations; forms the lowest percentage group of workers in the state; has helped make WA the only Australian state to expand its emissions since 2005; and has raised the possibility of environmental risk offshore, then where is the benefit to the people of WA and, indeed, Australians across the country?

During his reflections overlooking Fremantle, Tom Keely, Winton’s hungover hero, resorts to cynicism. A man who has burnt out trying to protect the state’s environment, he concedes that, for all the wealth mining has brought the state, WA is just a “philistine giant eager to pass off its good fortune as virtue.” It remains to be seen as to whether the gas industry will bring further good, or ill fortune to WA.