In May last year, while surfing a large swell off the east coast of Australia, surfer Al Cook was knocked unconscious by his board and disappeared under the waves. He was eventually found and rushed to shore by fellow surfers on a jet ski. Unresponsive, the group – including paramedics and lifeguards – worked on him and eventually saved his life.

Burleigh’s Jay Thompson was there that day, and the incident crystallised to him the importance for all surfers to have rescue and first aid knowledge. Jay is an old friend of Dan Ross, a Patagonia Global Surf Activist and Big Wave Risk Assessment Group instructor. The pair recently discussed the evolution of heavy water rescue, and how all surfers needed to paddle out with a plan.

Jay 'Bottle' Thompson in Tasmania. Photo: Cameron Green.

Jay 'Bottle' Thompson in Tasmania. Photo: Cameron Green.

Dan Ross: How did you come to surfing, and what pulled you towards bigger waves?

Jay Thompson: I’ve lived on the Gold Coast most of my life. I spent three years on the World Tour and was lucky enough to travel the globe to some amazing locations. Sometimes you’re confronted by some larger waves and, all of a sudden… you’ve got a cold, and you don’t want to go out because it’s too big for ya! I’ve been going to Hawaii for a good 20 years, on and off. I’ve also been to Mexico, Puerto Rico a bunch and down to Shipsterns in Tasmania where sometimes you’re confronted with big, heavy waves. I’m definitely not renowned as a big-wave surfer, that’s for sure. I sometimes shit myself and think, “I’m way out of my depth!” but I like the intensity of being out there. When you walk away from those bigger sessions there is that feeling of accomplishment, even if you don’t get any waves.

I think I paddled out at Puerto Escondido about a year ago and it was like 20-foot. Everyone was on their 10’0”s with the full Patagonia PSI Vest while I had an 8’0” and an Impact Vest. I caught one eight-footer, just to come in on! It was still good to be out there. It puts you in your place, you know? You feel completely humbled, at the mercy of Mother Nature and what she wants to do with ya.

There’s also that connection to the crew who you share those moments with, too. I know we’ve been in some heavy water situations together. It’s like, even if you haven’t known those people for a long time, when it’s big and everyone is looking out for each other, you come in buzzed from that. It’s a lot to know that friends are there to help you out if you get into a situation, that they’ll put their life on the line too. That’s a pretty cool thing to experience.

Jay: Hundred per cent. It’s weird, the adrenaline is pumping through your body, you’re getting carried away by the intensity… but then there is that unspoken rule of looking out for each other. Knowing that something could go wrong and you’re always looking over your shoulder for anyone else out there. They don’t even have to be your mates.

As I’m getting a bit older and wiser – and now I have a family – I’m actually starting to think, what is my emergency action plan? I’ve been lifeguarding on and off for the last 15 years and I understand basic first aid and advanced resuscitation, but in saying that, when It comes to surfing rescues and picking people up efficiently on jet skis, it’s different to when you’ve got people on shore. I’m not that educated in it. A few situations that I recently went through, really prompted me to want to be much more efficient in the water. There are such a variety of scenarios that can come down on you, and a few of the locations I go to are pretty remote, so now I ask myself questions. Like I said, I’m getting a bit older…

Jay with his young daughter. Photo: courtesy of Jay Thompson.

Jay with his young daughter. Photo: courtesy of Jay Thompson.

You’re getting so old man.

I think anybody who wants to be more efficient in the water in an emergency situation, they could benefit from BWRAG summits. I’m not just talking about how it’s run by surfers, but also by lifeguards and medical people with decades of experience and knowledge on what to do when shit goes wrong. I think it’s a important pathway to take, especially for the younger generation, whether or not they’re going to surf places like Chopes, Pipeline and other waves with big consequences. You might be all right there, but do you know how to hold someone up? How you drag them in? How about if you’re by yourself? In your lifetime, you’ll probably get a life-or-death situation and it’s good to be able to instantly be hands-on and know how to help.

It’s been one of the biggest things for me, being involved with the BWRAG and being around people like Kohl Christensen and Brian Keaulana. They’ve had that many experiences in intense situations. For me, being able to have that little bit of extra knowledge and practice some scenarios, means that when the real-life situation comes around, I can have the confidence to make the best decisions. The space is always evolving; they’re always learning new, more efficient techniques and the use of equipment. You mentioned you were wearing an impact vest when you were over in Puerto Rico, are you wearing one regularly these days?

You always think about, what if you hit your head and got knocked out? I usually use the vest when there are hold-downs or when it’s really thick and gnarly. On the Goldie, where there’s not many people around and if it’s cyclone season or I’m doing step-offs (from jet skis) and it’s up to my partner to pick me up, I’d definitely be wearing a vest. It wouldn’t even have to be that big and hairy nowadays.

We’re getting to the point of surfers becoming more aware. There have been a lot of lives lost, even people simply hitting their heads in light conditions. We owe a great many lives to the surfers who took helmets and vests from being ‘uncool’ into the mainstream.

Like you’re getting at, if you hit your head or black out in some way, it’s so much harder for that person you’re with to try to find you if you’ve got no flotation. Or even worse, if you break your leggy at the same time and the board isn’t there, that adds a whole other level of complexity. Which ties into a story you recently shared, can you run us through what happened?

It was a late-spring afternoon session at a location that’s pretty remote. You’re actually quite far out to sea, probably a kilometre, and there’s nothing around on shore, just sand dunes. The closest port-of-call would be a 20-30 minute jet ski ride. We were up there and it started out pretty flawless, one of those days. There were six skis out and it was anywhere from six-to-10-foot with the odd bigger one. The wave is sort of like… if you can picture Sunset, but a bigger, broader surf zone. It’s like going from the top of Backyards down to Sunset, a really big wide berth, anywhere from 500-to-800-metres across with different peaks along the sand bank.

I was with my mate on a ski and it got really thick that afternoon. I got one or two crazy ones – some of the better waves I’ve caught on the coast. You get caught up in the moment and then, I caught this other one. I was trying to get deeper and deeper and pulled in. It was one of the gnarliest waves and I had the most ferocious wipeout. I said, “Geez, we better pump the breaks, it’s dangerous out here.” That wave clicked me into gear, thinking something could go pear-shaped and I started to keep an eye on everyone.

All of a sudden there weren’t six skis anymore. Something didn’t feel right. We waited about 30 seconds, looked around and thought, “Let’s start making our way in.” I saw a photographer on the inside of the break; he said he’d just lost his housing, so I thought maybe the other skis were looking for that. That’s when we saw a couple of skis shooting towards the shore.

When we got to the beach Al Cook was out cold and convulsing. An off-duty paramedic had been out with us and he was giving him compressions, rolling him back and forth using a paramedic technique – they couldn’t get an airway, he had so much water in his lungs. Coughing and splattering but in a completely unresponsive state, there was a huge gash on the side of his head. The snapped leg-rope was still on his ankle.

What actually went down was Al took a wave, went under, and the board hit him in the jaw and ear, knocking him out. Al’s jet ski partner, a really experienced driver and life-long surfing mate, had miraculously spotted a few inches of his board and jumped off to grab him because he couldn't do it from the ski, but then a trio of 10-foot waves came in and he lost him. At this point the driver was diving under and searching but just couldn’t find Al. He must have gone over the falls before being held under. One of the other guys on the skis was coming in to pick up his own partner and saw a jet ski upside down, so he diverted. This second jet ski managed to scoop up an unconscious Al and get his head out of the water. Now, a third jet ski, with the off-duty paramedic noticed and joined them. He was like, “Look, he’s out, don’t stuff around. We gotta get him straight to shore.” And then they just pinned it in, which, like I said was a bit of a mission. As soon as they got to the beach, they dragged him up and started to work on him. That’s where we caught up.

It was really lucky that the paramedic was there and also a couple of other fellas who were lifeguards and fireys. We had four people on the scene who knew a lot about what they were doing. Still, things were touch-and-go for a while; there were times when he wasn’t breathing. We phoned to get him airlifted out, and in the meantime the Volunteer Marine Rescue came along, including another paramedic who helped get him in a semi-stable condition. It was a cold day, maybe 8˙C. He was freezing, so we wrapped him in everything we had and some fishermen even threw jumpers overboard to us. It was getting dark when the air ambulance arrived. He ended up in the ER and hospital for a couple of days but he pulled through. Looking back, it really was crazy so many of these elements came together in our favour.

Sounds like there were a couple of knowledgeable people there, but even in just playing a support role, it’s valuable to understand what’s going on, how to make the responders’ jobs easier and how to make sure you’re not getting in the way.

I guess that’s something evident in what BWRAG’s teaching – that when you’re in those life-threatening situations it’s a team effort. You can all play your part. After that incident the off-duty paramedic and I debriefed on what went down. I was asking, “Was there anything more we could have done?” We talked about maybe having a defibrillator nearby, brushing up on jet ski retrieval skills. And the big one, understanding what our emergency action plan was. Like, “Okay, what is one of the worst-case scenarios that we could up against at this location? What do I do? Have we got the safety measures and gear in place, even if it’s as simple as a first aid kit, a flare, a charged phone… are we confident in CPR and first aid?” We could have saved some more time if we were all more practiced, which is where the BWRAG course could be really helpful to a lot of people. Little things make a huge difference.

Al Cook surfing at the site of the incident. Photo: Andrew Shield.

Al Cook surfing at the site of the incident. Photo: Andrew Shield.

How did you guys feel afterwards?

We talked about it. For me, watching the crew out there, a lot of good things have come out of it. There is no way I’d go up there solo now. I’d make sure to have two or three other skis with support crew, keeping an eye out for one another. And when you’re out there, often you don’t know everyone, but if you just have that initial chat and check-in and keep an eye-out for each other, I think that is a big thing as well.

Those lines of communication, even non-verbal communication, are important. Like you said, you could be way, way up the point and you’re not going to be able to hear, only read signals about what’s gone down. Even in spots where it might not be that big, some of those waves you’re surfing have a lot of power and you can get yourself in life-threatening spots.

Right! People associate the BWRAG with just big waves, but it’s not only about that. A few Burleigh locals might remember a couple of decades ago, a guy got a fin to the gut and his intestines were hanging out and he was basically unconsciously floating on in the inside. One of the guys grabbed him and helped out. Regardless of the size of the wave, you’re going to come up with scenarios and it’s good to know the steps required.

[Editors note: Al Cook added a poignant insight while reviewing this story ahead of publishing. "Something I learnt that day: it's easy to be the one dying. You don’t really have any pain or understanding of what is going on. It’s the long-term effect on the other people there. Your family, friends, rescuers putting themselves in harm’s way. People have a responsibility to think about this a bit before they charge off. Have an emergency plan, wear a flotation vest, know a bit of first aid/rescue and plan for the 'what ifs'. Don’t do it for yourself, but do it for the sake of the other people that are going to have to deal with the mess if, when, it all goes pear-shaped.]

Talking water safety with some groms at Duranbah (D-Bah). Photo: courtesy of Jay Thompson.

Talking water safety with some groms at Duranbah (D-Bah). Photo: courtesy of Jay Thompson.

Jay, you’re also a coach of younger surfers as well. It’s pretty cool to think about the kids under your guidance getting your decades of ocean knowledge and lifeguarding experience.

Yeah I am. When the waves are small, we’ll do some fun little rescue drills with the younger crew, similar to what you do at nippers with a ‘patient’ out in the water. They’re having fun at training and my hope is that they might be able to use those skills one day, if they’re ever in need.

Find out about the Big Wave Risk Assessment Group here.

More from Patagonia Surf.

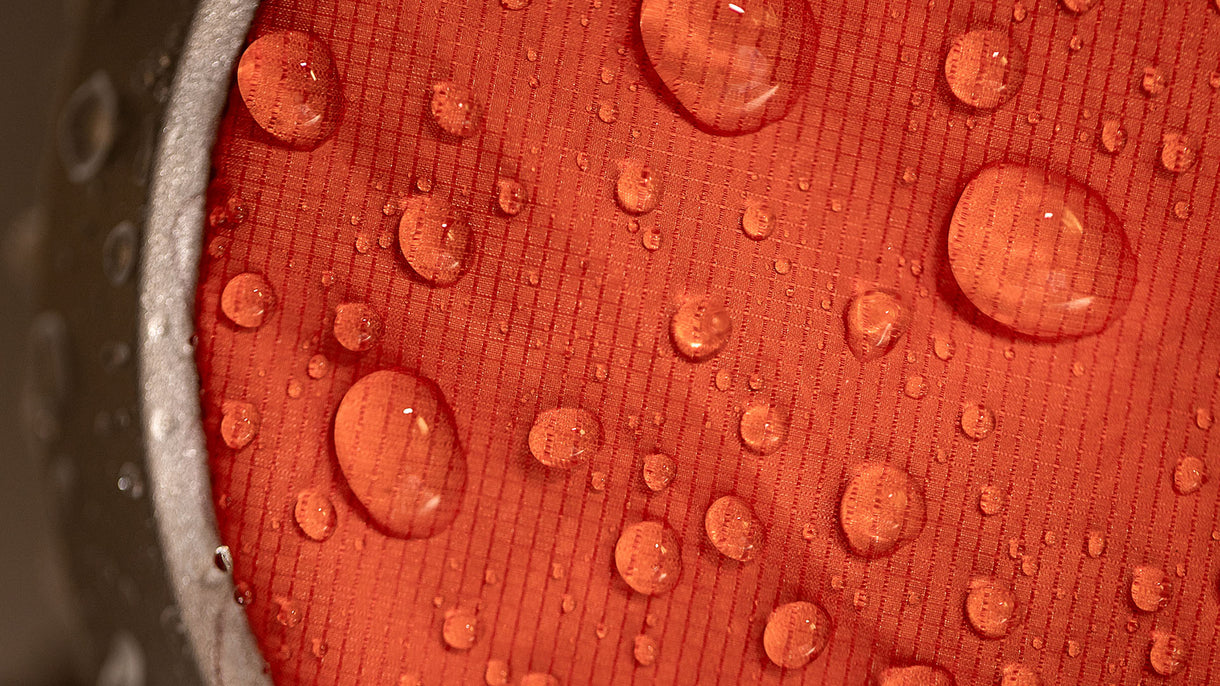

Banner image – Jay 'Bottle' Thompson surfing at the site of the incident. Photo: Andrew Shield.

____________________________________________________________________

Author Profile