All photography by Charlotte Wighton.

Earlier this year, we experienced the largest flood in colonial history. When it hit us, it hit hard. The rain started falling on February 28 and continued to fall, heavy and constant. Here in Northern NSW, the waters rose and the rain didn’t stop. By March 1 the region was devastated. There wasn’t much time to think; everyone responded instinctively with their skill sets. I am a proud Bundjalung woman and I knew that in a time like this I had to support my community. Of course, right? Yes, but beyond that, if we didn’t support them, who would?

Historically, the relationship in this country between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people has been bleak to say the least. It began with the land being stolen, an attempted genocide of our peoples, and children and women being taken away from families and communities.

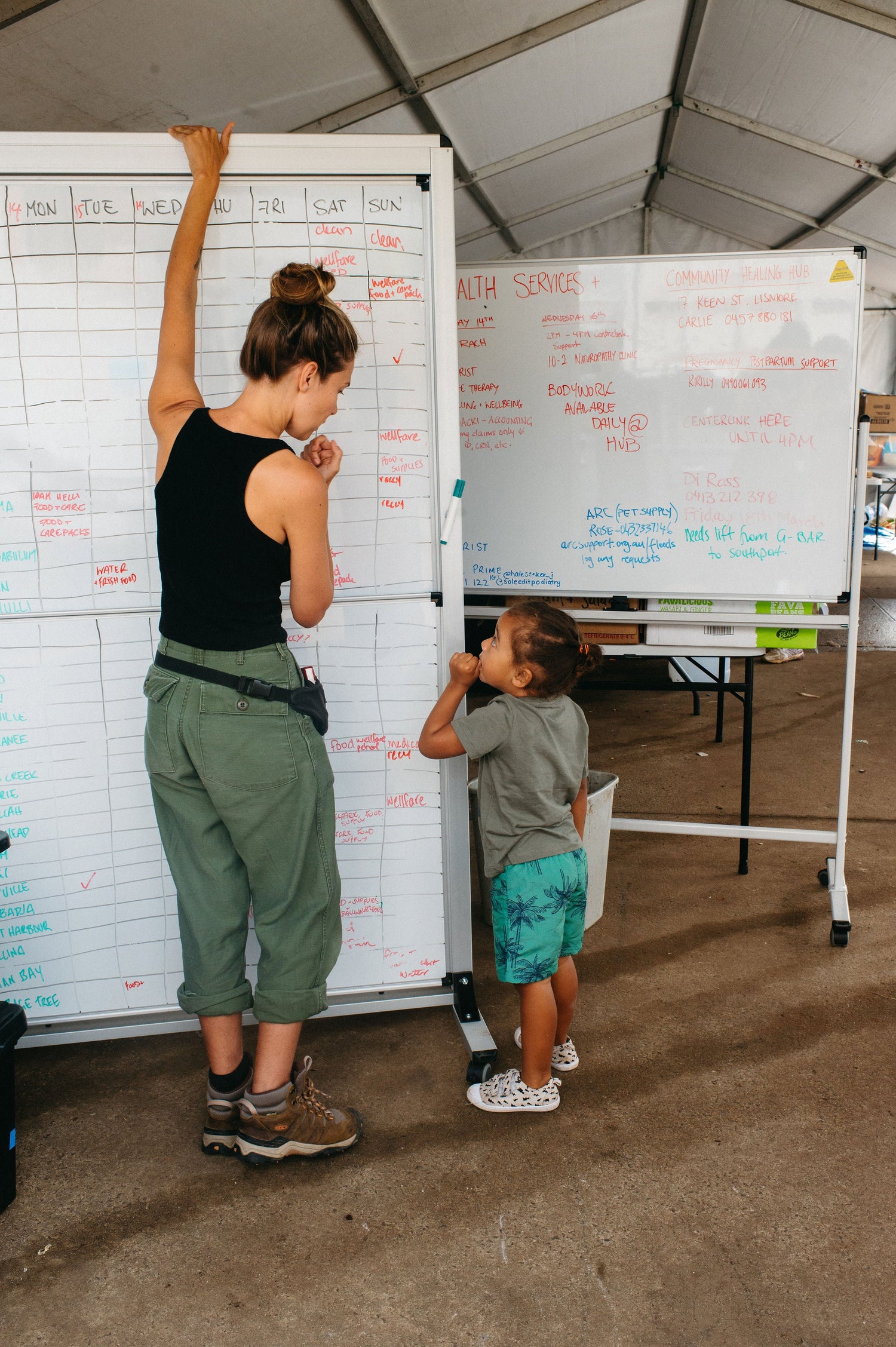

Today, not much is different. The land is still stolen, the genocide continues and the government is still taking our children away. The pressure of the dominant culture impacts our ability to practice culture. We are denied access to land and denied basic access to affordable healthy foods. Things haven’t changed in this country, and why would they when it is still being run by the colonisers? It's time to turn the tables. Indigenous people deserve respectable roles in our society. They deserve to be leaders and they will lead better than we will ever know. Just look at the example of the Koori Mail Flood Hub.