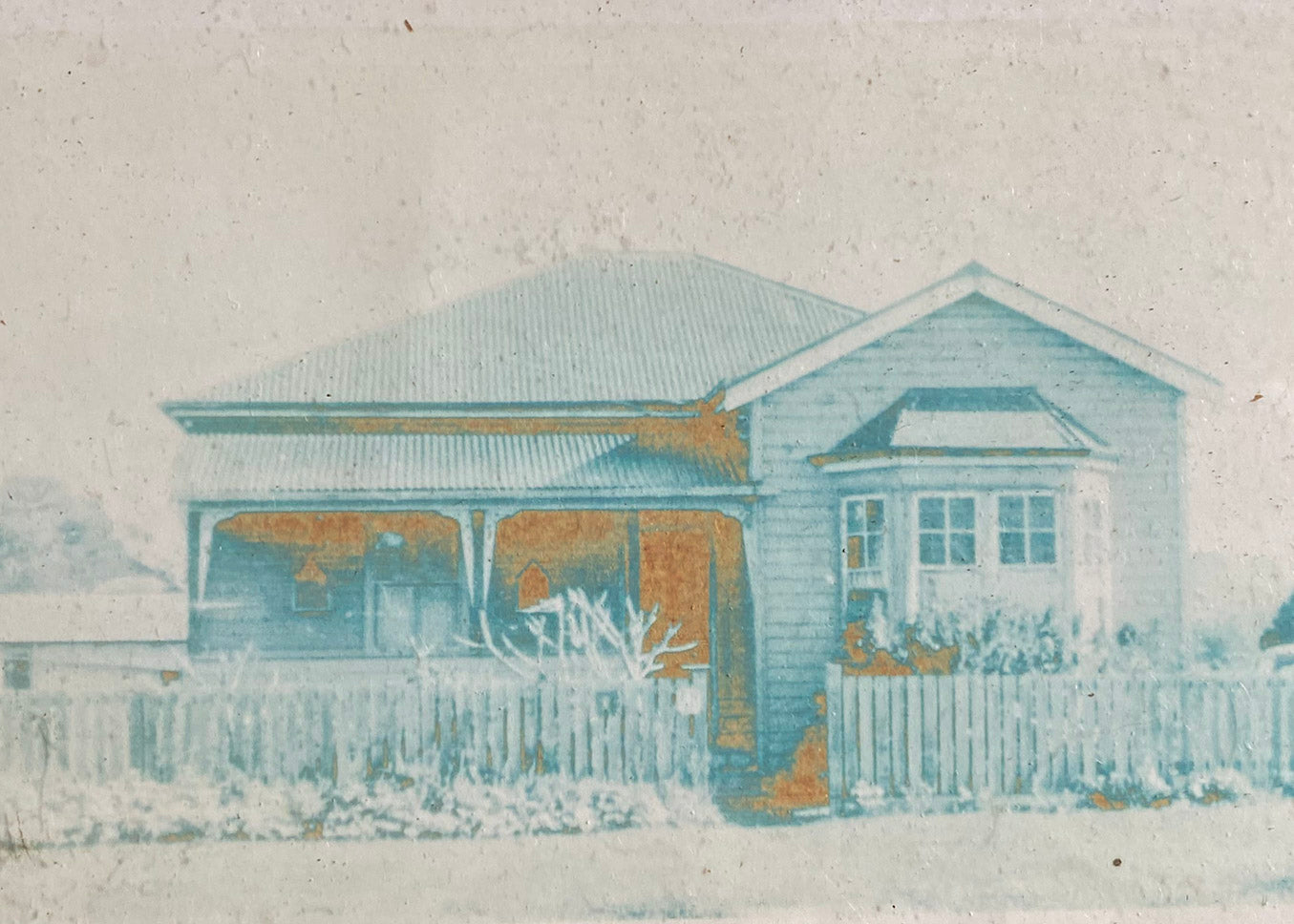

We bought our hundred-year-old blue house on a handshake in the surf, then spent the better part of a year on hands and knees, grappling with dirty, weathered flooring. We peeled back layers of lino and pried metal staples and nails, and sanded and polished to reveal beautifully weathered, maple-tinted timber lengths.

Over the past century, the house had been many things to many people: a doctor’s surgery, a salon, and a notoriously wild party container. The floors were a lasagne of stories: happy feet scuffing, sticky feet playing, solemn feet carrying the weight of a diagnosis. We ripped out walls, added big glass doors and have generally tried to let the light spill in – to add a new story, another layer.

The largest piece of art that hangs on the old walls’ new grey-blue facade is a geometric acrylic painting of a mother and calf humpback by local activist/artist Howie Cooke called Night Reef Whales. Cetaceans soaring through deep ocean – it’s serene.

In the mid-1900s, the Bienke family made this house a home for a couple of generations. Their patriarch was a timber cutter turned third generation fisho who made his early living in Byron Bay, handlining for snapper and pearl perch and baiting leatherjackets with fresh horse meat.

In between building the vessel Dorothy-June for the family business, one of the Bienke sons, Brian, needed work. Back then, Byron Bay was a blue-collar industrial town: sand mining, logging, dairy, the abattoir, and from 1954 to 1962, whaling. It was taxing, gruesome work, extracting oil from whales: 12-hour days, seven days a week off the old jetty and at the station where more than a thousand whales were processed.

“It was good pay,” Brian Bienke recalls in the published collection Old Stories from Byron Bay. “But you’d come home, and you’d have to get in the bath, and you’d leave a ring of fat all the way around. You stunk like whale. So, it got into the pores of your skin and everything, you know, the oil.” I imagine Brian’s slippery boots tromping across these timber floors on the way to the washroom, shining the grain with fresh humpback blubber after a too-long day at the factory.

Residents say the boom of the harpoon once echoed through the town. Later, the stench.