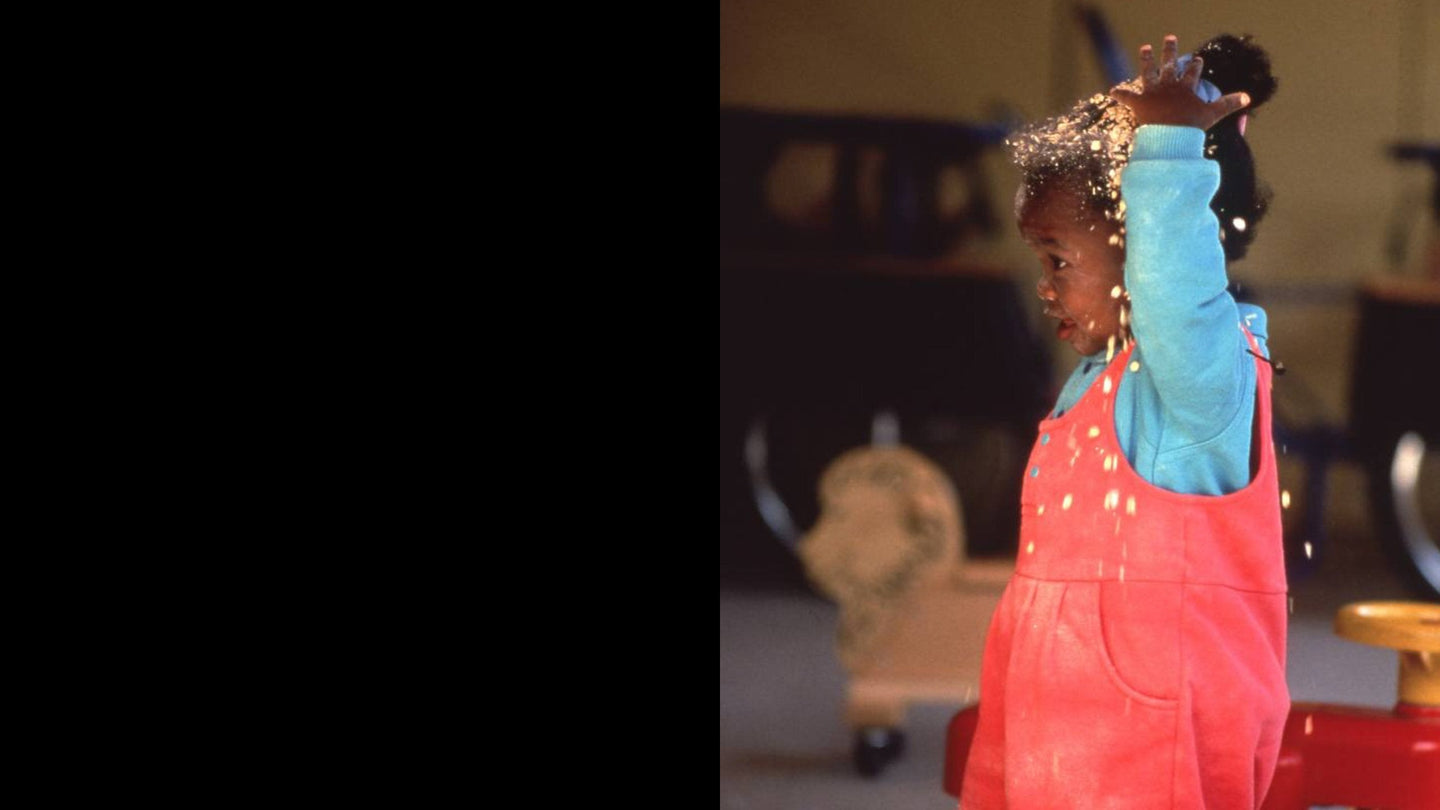

Yvon Chouinard (far right), Patagonia’s founder, got his start as a climber in 1953 as a 14-year-old member of the Southern California Falconry Club. One of the adult leaders, Don Prentice, taught the boys how to rappel down the cliffs to the falcon aeries. This simple lesson sparked a lifelong love of rock climbing in Yvon.

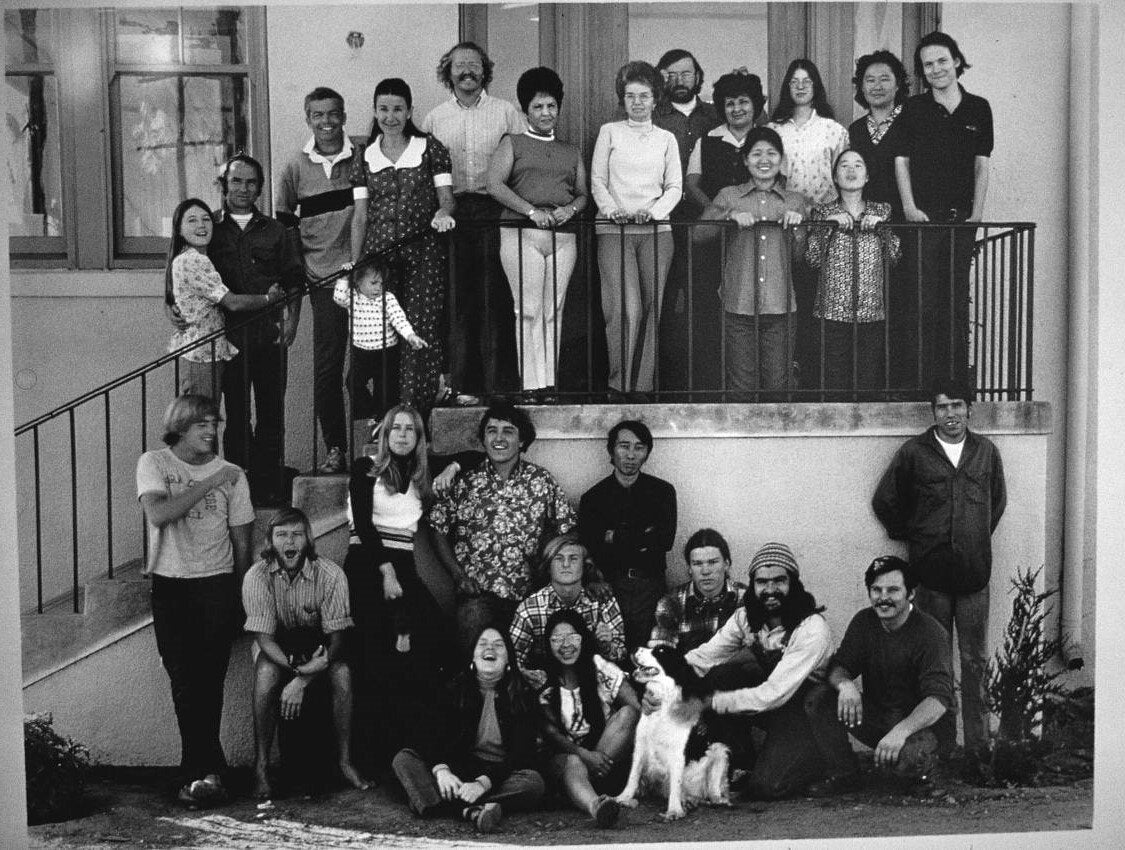

Chouinard started hanging out at Stoney Point and Tahquitz Rock, where he met some other young climbers who belonged to the Sierra Club, including T.M. Herbert, Royal Robbins and Tom Frost. Eventually, the friends moved on from Tahquitz to Yosemite, to teach themselves to climb its big walls.

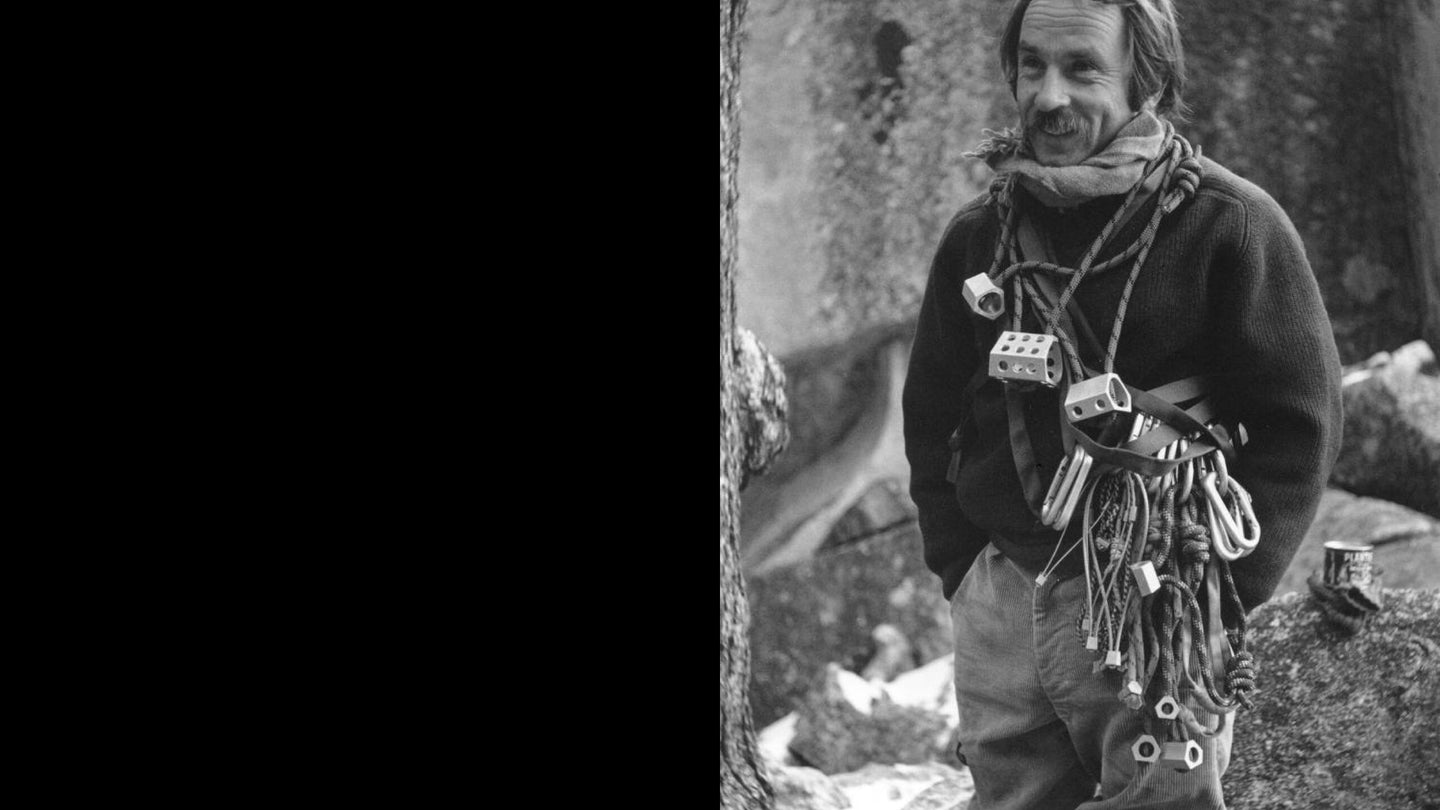

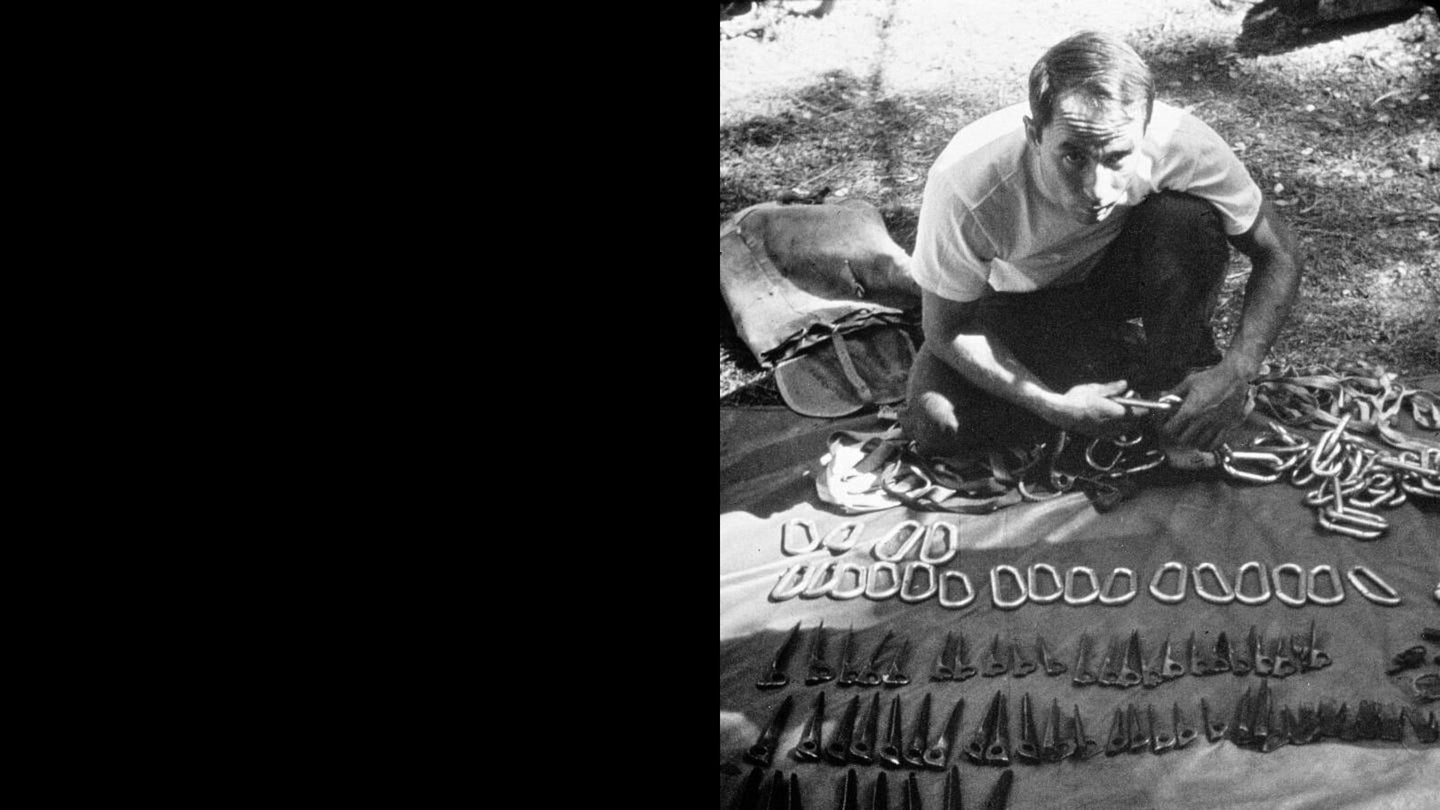

In 1957, Yvon went to a junkyard and bought a used coal-fired forge, a 138-pound anvil and some tongs and hammers, and started teaching himself how to blacksmith. Chouinard made his first pitons from an old harvester blade and tried them out with T.M. Herbert on early ascents of the Lost Arrow Chimney and the north face of Sentinel Rock in Yosemite.

The word spread and soon friends had to have Chouinard’s chrome-molybdenum steel pitons. Before he knew it, he was in business. He could forge two of his pitons in an hour and sold them for $1.50 each. Chouinard built a small shop in his parents’ backyard in Burbank. Most of his tools were portable, so he could load up his car and travel the California coast from Big Sur to San Diego, surfing.

He supported himself selling gear from the back of his car. The profits were slim, though. Before leaving for the Rockies one summer he bought two cases of dented, canned cat tuna from a damaged-can outlet in San Francisco. This food supply was supplemented by oatmeal, potatoes and poached ground squirrel and porcupines.

In Yosemite, he and his friends had to hide out from the rangers in the boulders above Camp 4 after they overstayed the two-week camping limit. They took pride in the fact that climbing rocks and icefalls had no economic value; that they were rebels. Their heroes were Muir, Thoreau, Emerson, Gaston Rébuffat, Riccardo Cassin and Hermann Buhl.

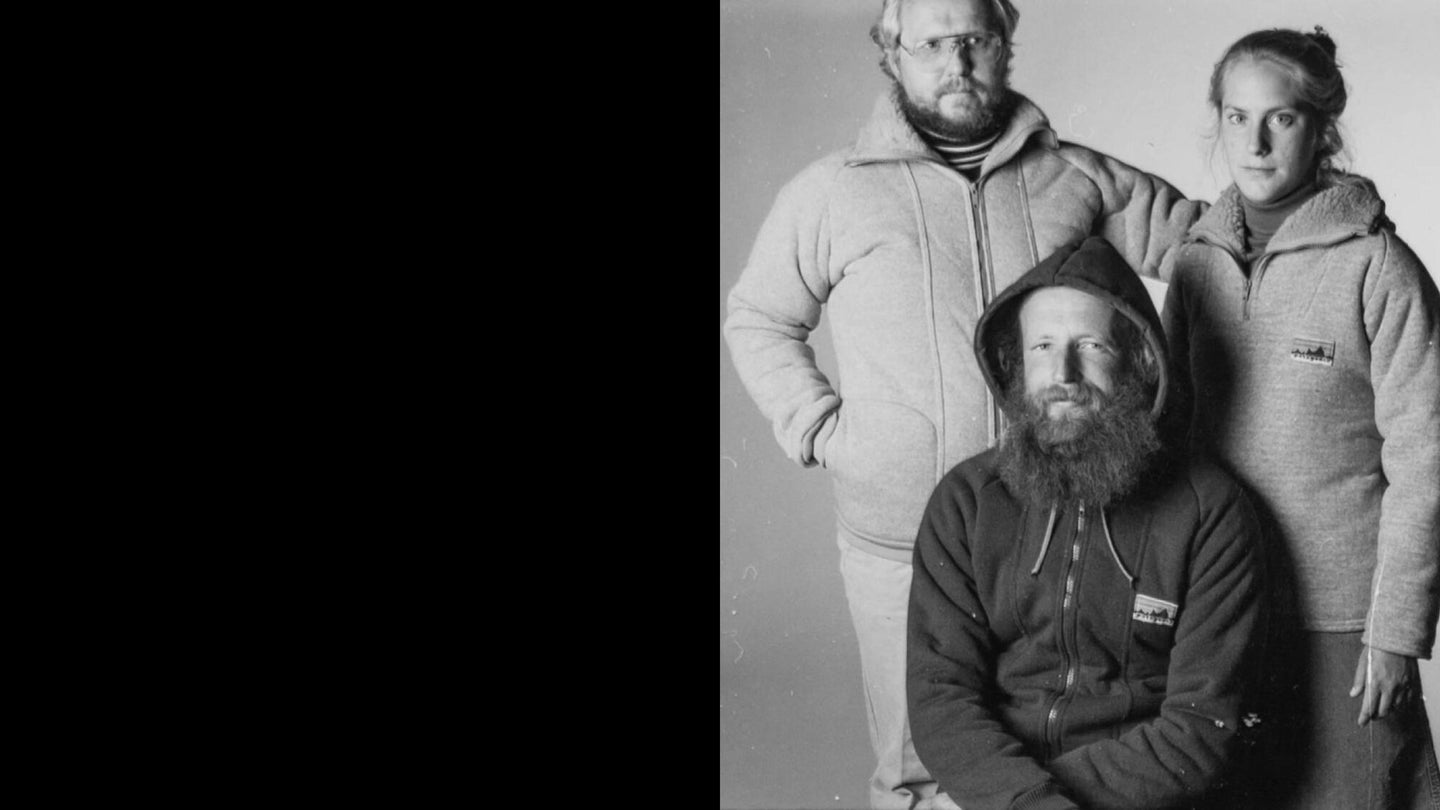

In 1965, Yvon went into partnership with Tom Frost and started Chouinard Equipment. During the nine years that Frost and Chouinard were partners, they redesigned and improved almost every climbing tool to make them stronger, lighter, simpler and more functional. Their guiding design principle came from Antoine de Saint Exupéry, the French aviator: “In anything at all, perfection is finally attained not when there is no longer anything to add, but when there is no longer anything to take away, when a body has been stripped down to its nakedness.”

Excerpt from WIND, SAND AND STARS, copyright 1939 by Antoine de Saint Exupéry and renewed 1967 by Lewis Galantiere, reprinted by permission of Harcourt, Inc. This material may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form without the prior written permission of the publisher.

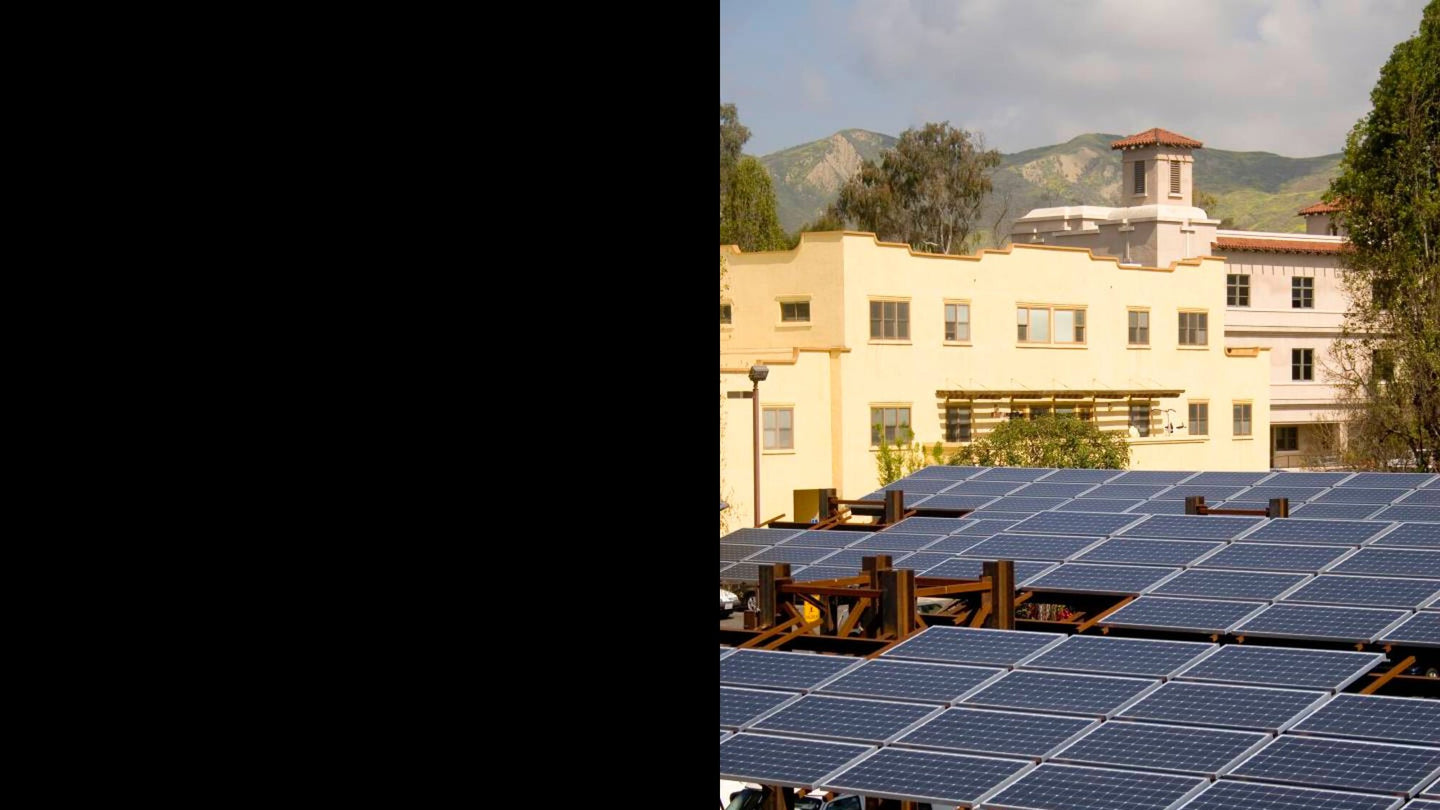

By 1970, Chouinard Equipment had become the largest supplier of climbing hardware in the United States. It had also become an environmental villain because its gear was damaging the rock. The same fragile cracks had to endure repeated hammering of pitons during both placement and removal, and the disfiguring was severe. Chouinard and Frost decided to minimize the piton business. This was to be the first big environmental step we would take over the years.

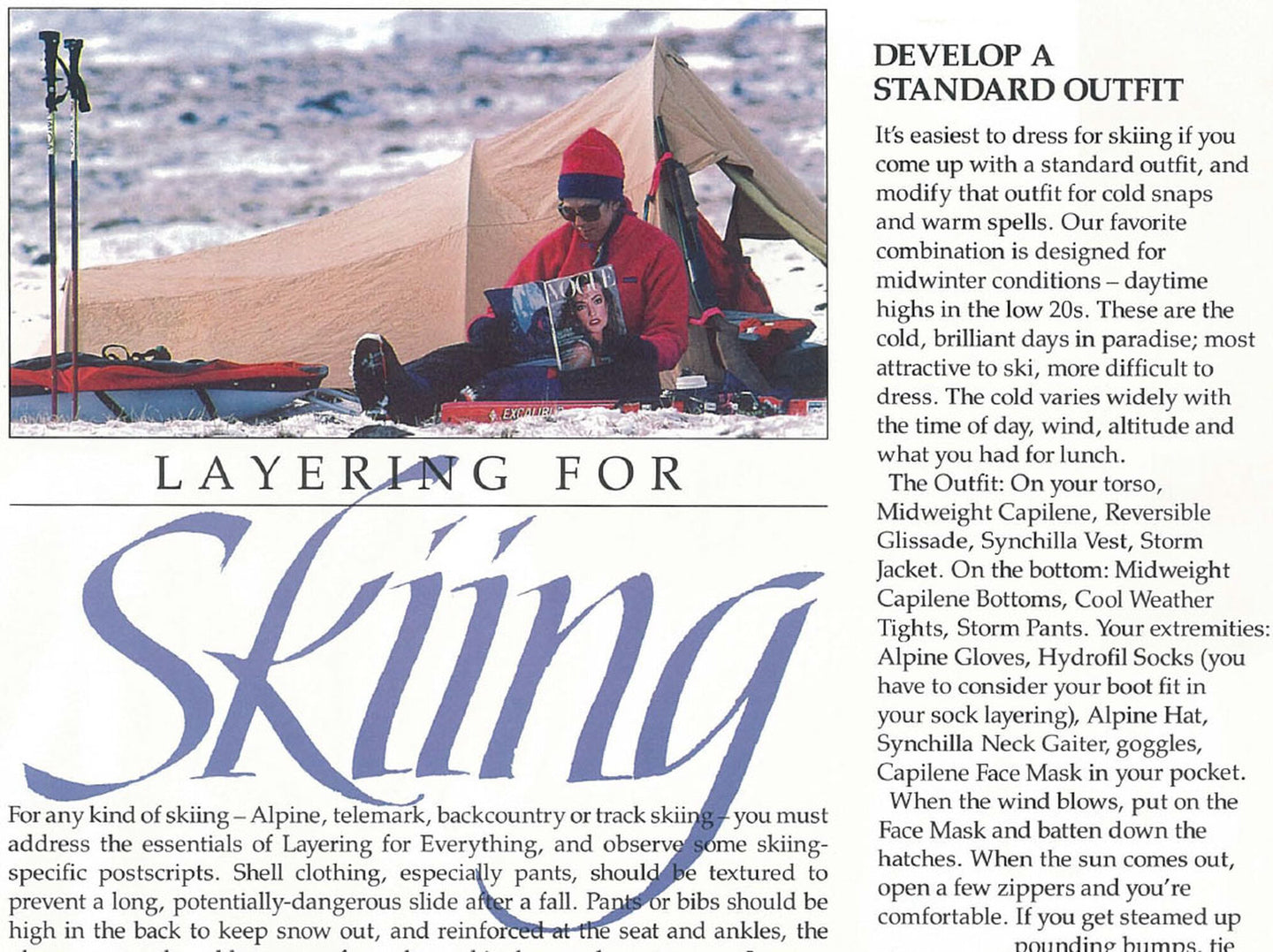

Fortunately, there was an alternative: aluminum chocks that could be wedged by hand rather than hammered in and out of cracks. We introduced them in the first Chouinard Equipment catalog in 1972. A 14-page essay by Sierra climber Doug Robinson on how to use chocks appeared in the catalog, paving the way for future environmental essays in Patagonia catalogs. Within a few months of the catalog’s mailing, the piton business had atrophied; chocks sold faster than they could be made.