I was standing with three friends at the top of a cliff near Mundaka, one of the world’s most iconic surf spots. We watched in horror as a gigantic black stain advanced its way towards the coast. Minutes later, the waves started dumping millions of blobs of crude oil onto the shoreline. In the space of a few hours, the beautiful coastline of yellow sand had turned into a stinking carpet of black, sticky tar.

There would be no surfing for the rest of the winter, and no fishing for nine months anywhere in the Bay of Biscay. Hundreds of thousands of birds and other creatures would die, and the ecosystem would be altered forever.

The oil had come from a supertanker called the Prestige, which had broken up in heavy seas off Galicia about two weeks before. The oil had spread all the way along the north coast of Spain and down into Portugal, and would soon work its way up the French Biscay coast and beyond.

The area nearest to the spill – ‘ground-zero’ – was the Costa da Morte, an extraordinary stretch of unspoilt coastline in the far northwest reaches of Galicia. The Costa da Morte is wide open to the North Atlantic and in winter receives some of the largest swells in the world. It is known as a magical place, with empty white-sand beaches, mist-shrouded cliffs and crystal-clean, cold water. But in December 2002 it looked more like a scene from a post-apocalyptic science-fiction movie.

The Prestige oil spill was Spain and Europe’s worst environmental catastrophe in living memory. After enduring the consequences of such a disaster, the people of Galicia set up a platform called Nunca Mais (never again) with a simple and clear objective: to do everything possible in the future to keep oil away from their coastline.

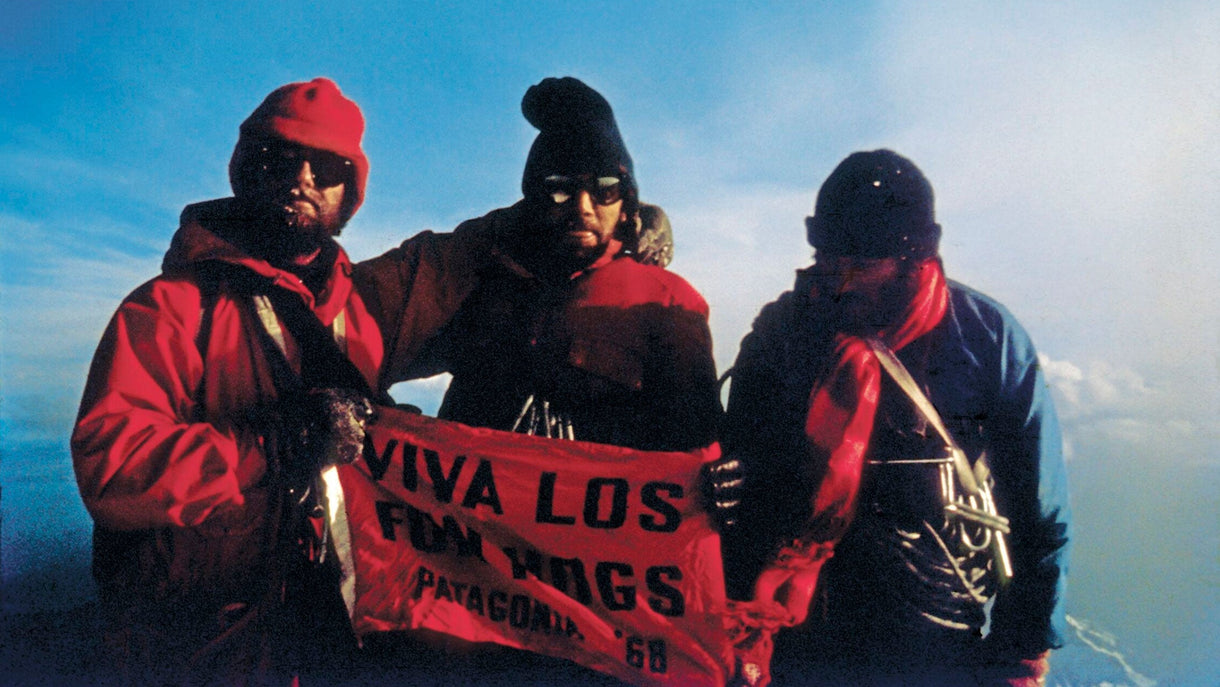

Cleaning up the Prestige oil spill in Galicia. Photo: Stephane M Grueso

Over on the other side of the planet, there is a stretch of coastline similar in many ways to Galicia, although much, much bigger. The coast around the Great Australian Bight, including southern WA, South Australia and Victoria, is harsh and unspoilt. It contains the Bunda cliffs, the world’s longest uninterrupted sea cliffs, and dozens of epic surf spots, many of which are hundreds of kilometres from the nearest town.

The Bight itself is one of the world’s most unique and productive marine ecosystems, with 19 marine parks and several marine reserves. Around 85 per cent of the species found there are not found anywhere else on the planet. Year-round open-ocean wave heights in the Bight are close to the highest in the world, frequently exceeding 15 metres.

The big difference between here and Galicia is that the people living along the coast of southern Australia haven’t had direct experience of a major oil spill on the scale of the Prestige. Hopefully they never will.

Great Australian Bight, South Australia. Photo: SA Rips

Great Australian Bight, South Australia. Photo: SA Rips

You see, a Norwegian oil company called Equinor (formerly Statoil) wants to drill for oil in the Great Australian Bight, 370 km offshore. The oil platform would be a floating one, with stabilisers to deal with the constant massive swells and storm-force winds. The ‘drill bit’ would be five or six kilometres long, first to reach the sea bed, 2,000 metres down, and then to reach the oil, another three to four kilometres below the bed. Equinor assures us that all this is totally safe:

“It is important to understand that the chance of a major oil spill is very low and we will not drill unless we believe we can do it safely. We have done extensive research on the geology in the area and the metocean conditions, and found these are well within the range where we’ve safely operated before.”

On the other hand, marine conservation biologist Professor Richard Steiner, who has done an independent risk assessment, points out:

“Given the extreme depths and uncertainties in oil reservoir characteristics involved, this should be considered a high-risk project. Regardless of the safeguards employed […] the risk of a blowout and large oil spill is very real.

“As someone who has studied these disasters around the world, and heard the endless misrepresentations from industry about all this, I would respectfully advise that the risks of deep-water drilling in the Bight greatly outweigh potential benefits, and a no-drilling decision would be a wise course for a sustainable future for southern Australia.”

Originally, Equinor was in partnership with BP and Chevron, but both of those companies backed out, for reasons that they haven’t made very clear. Just in case you didn’t know, BP was responsible for the biggest oil spill in history: the Deepwater Horizon. The Deepwater Horizon oil platform was located in the Gulf of Mexico, a shallower, less remote and much calmer location than the Great Australian Bight.

Heavy seas in the Great Australian Bight. Photo: SA Rips

So, what if the unthinkable happened? What would happen if they went ahead with the project, and then there was an oil spill?

Well, according to several simulation models and calculations, including those undertaken by BP and Equinor themselves, the oil would first spread over thousands of square kilometres of offshore water, and then it would reach the coast, affecting southern WA, South Australia, Victoria, Tasmania, NSW and even New Zealand. In a worst-case scenario, the amount of oil spilled could exceed seven million barrels (about a million tonnes). That’s twice as much as the Deepwater Horizon and 20 times the Prestige.

If that happened, the ecosystem would be permanently affected. Hundreds of thousands of birds and fish would die, kelp ecosystems and other shoreline communities would be damaged, and you could say goodbye to thousands of whales, dolphins and other mammals. Some species would probably disappear forever.

People’s lives would be seriously affected, with human coastal and offshore activities ceasing altogether. Reefs and beaches would be covered in oil, and surfing would be out of the question. Most of the cleaning up would probably be done by local communities.

According to Equinor, there won’t be a spill. But if there is one, everything will be alright:

“In the highly unlikely event there is a spill, our priority will be to stop and contain it before it reaches shore. We are also working with state agencies along the coast to make sure a good shoreline response plan is in place.”

In other words, there definitely won’t be a spill, but there might be. And if there is one, it definitely won’t reach the shore, but it might do. And if it does, we’ll make sure other people clean it up.

Professor Steiner puts it in clearer terms:

“Once oil is spilled, the damage will be done regardless of response efforts. Spill response in the Bight would likely recover less than five per cent of the total spilled, particularly given the exposed, high energy environment of the offshore region. Chemical dispersants would at best be ineffective, but more likely would compound ecological harm to offshore waters. The oil industry knows all this, but seldom admits it.”

Equinor's oil spill modelling. Graphic: Greenpeace

But there is another argument for not drilling. In a time when we should be doing everything we can to put the brakes on climate change and planetary destruction, why the hell are we still digging for fossil fuels? Instead of using technology to develop forms of energy that don’t jeopardise the future of our species, we are using it to extract fossil fuels in ever more risky places using ever more desperate methods (read tar sands, fracking). Drilling for oil in ridiculous places like the Great Australian Bight is no exception.

In a famous 2012 article, climate scientist Bill Mckibben referred to a simple mathematical exercise. If we burn more than 20 per cent of the existing fossil fuel reserves, global warming will shoot above 2°C, and we will be facing irreversible climate catastrophe.

In the seven years since that article was published, things haven’t improved. The Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC) now suggests that climate change will shift into runaway mode if we exceed 1.5°C, not 2°C. In other words, if we don’t act right now, the shit will hit the fan sooner than we thought. The IPCC now estimates that, if we continue as we are, we will hit 1.5°C in about 12 years’ time.

Meanwhile, companies like Equinor are still looking for new and more risky places to squeeze that last drop of oil out of the ground. There is no mention anywhere of stopping at 20 per cent. Of course they won’t stop, not in their wildest dreams. Unless we stop them.

In the words of Bill Mckibben:

“The fossil-fuel industry has become a rogue industry, reckless like no other force on Earth. It is Public Enemy Number One to the survival of our planetary civilisation.”

Pristine waters of Victoria. Photo: Jarrah Lynch

Who, exactly, will benefit if Equinor drill for oil in the Great Australian Bight? The people of southern Australia? The fishermen? The surfers? The First-Nation communities? The whales?

No, none of them. It will be a small group of greedy men and women who are addicted to money, status and power, via oil. But they won’t even benefit in the long run, because their addiction is destroying the planet’s natural resources (air to breathe, water to drink and food to eat) and it is making the planet uninhabitable for future generations, including their own children and grandchildren.

On the other hand, if they don’t drill, the probability of an oil spill disaster like the Prestige or the Deepwater Horizon will be zero. A pristine part of the planet and the habitat of humans and other species will have been conserved for the time being. But crucially, it might just send a message to other companies like Equinor: If we stop this extractivist frenzy and think again, we just might be in time to save humanity.

If we all get together and stop Equinor drilling in the Great Australian Bight, everyone will benefit. Otherwise, a group of surfers might soon be standing on the cliff at Bell’s Beach, like I was 17 years ago, watching in horror as the first waves of crude oil start coming ashore.

Please help to stop this madness. Put pressure on the company by submitting your comments before 20th March

Learn more about the issue HERE

About the Author-

Tony Butt holds a BSc in Ocean Science and a PhD in Physical Oceanography. He divides his time between Northwest Spain and Southwest South Africa; makes a meager living teaching and writing about waves and the coastal environment; and works with NGOs like Surfers Against Sewage and Save the Waves. His published books include Surf Science: an Introduction to Waves for Surfing (2014), The Surfers Guide to Waves, Coasts and Climates (2009) and A Surfer’s Guide to Sustainability (2011).