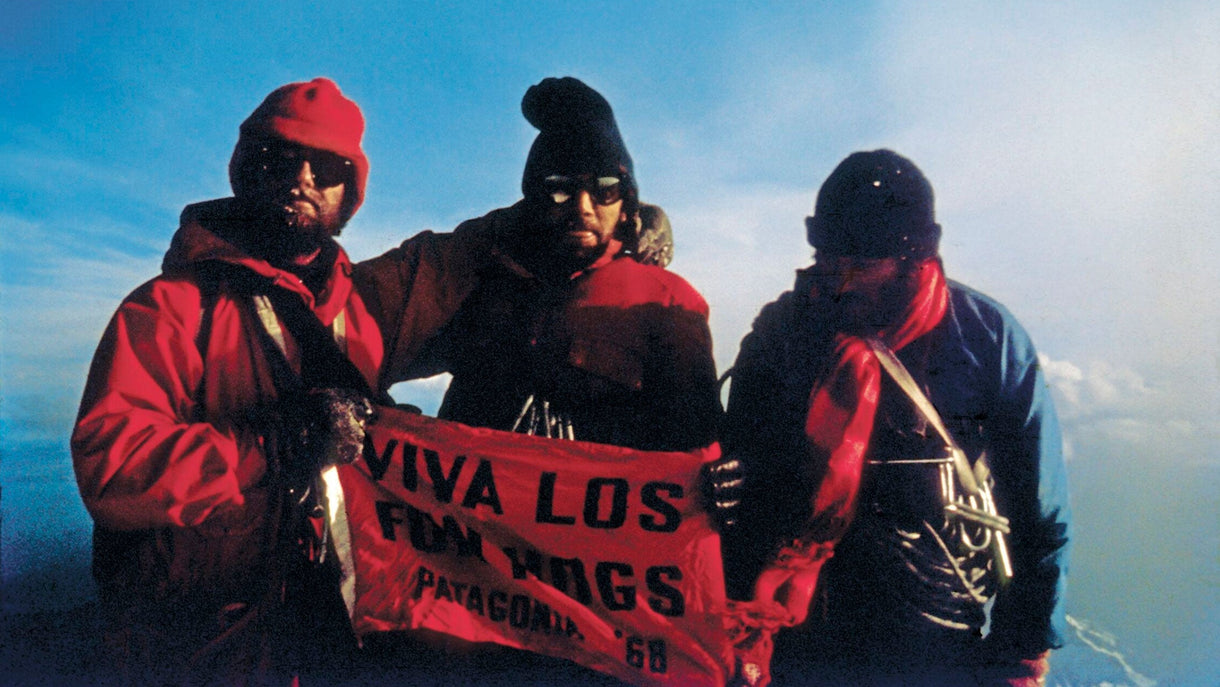

All photos and captions by Matthew Tufts

“Perhaps we should consider roping up again.”

The last light of a milky grey day had long since faded. Everett and Tristan chuckled behind me as I pulled myself from the crevasse I’d plunged into up to my thighs. Sleep deprivation has a way of making poor choices seem funny, and we were 46 miles and 16 hours into a seriously questionable venture, which I’d dubbed “The Selkirk Shwack.”

I’ve always taken a creative approach to running, influenced by my background as a skier. In the ski world, routes are rarely rigidly defined; rather, they are malleable. You find your own line, working with the terrain as subtle contours reveal themselves in real time. I’m often trying to tap into that same experience through running. Unsurprisingly, strictly defined “trails” and “running” have become increasingly absent from my itineraries. The vulnerability of traveling light—a simple vest, a pair of shoes, a warm layer and minimal technical gear—cultivates a profound feeling of connection with the land. Listening isn’t an option but an imperative. The more you do so, the more fluidly you can move through complex terrain.

Moving fast and slow at the same time. Several hours later, it would be dark and we’d be forced to jump crevasses by headlamp.

The Selkirk Shwack was perhaps the loosest interpretation of trail running I’d yet imagined: A west-east traverse of the Selkirks north of Revelstoke, British Columbia, linking the “big bend” of the Columbia River from Lake Revelstoke to the eastern arm of Kinbasket Lake. The Selkirks are defined by steep, vertical relief above glacial river valleys, and my proposed route would take us past some of the most impressive peaks in the range. I estimated 50 miles and 16,000 feet of vertical gain and descent.

I’d recruited two local endurance crushers to join me: Everett Craig, a Revelstokian who spends winters hut-keeping at a remote lodge in the Selkirks, and Tristan Kodors, a splitboarding guide from Nelson, BC. They had no idea what they were getting into, but, in fairness, neither did I.

Talus and slab never feels cruisier than when you’re about to depart onto a heavily crevassed glacier. Everett and Tristan enjoy a few dry, rocky miles on day 1.

We departed at 6 a.m. on a foggy late-August morning. After a 30-mile gravel ride down a Forest Service spur road, we switched to running shoes and began our off-trail adventure. We laughed our way up exposed waterfall gulleys and impenetrable thickets, across a bog, down a creek littered with bear tracks and up into the sub-alpine. Dense clag obscured most of the route ahead as we crested the ridgetop to peer across at the glacier below. We descended optimistically, a peculiar trio of runners in shorts and light puffies, roped up on a quarter-inch line, curiously tiptoeing around gaping maws rendered nearly indiscernible in the flat light.

By dusk, we were navigating the final glacial descent to our planned bivy spot. I leapt over a crevasse, only to plunge knee-deep into another. Startled, I mantled onto a rib of ice and pulled my foot out, shaking slush from my trail runners as I peered into the dark hole. Mount Sir Sandford, the tallest peak in the Selkirks, loomed behind us, guarded by broken icefalls and massive headwalls. I took a breath, thought about how much simpler this would be on skis, and then stood back up and followed Tristan’s bobbing headlamp toward the dark valley below.

The Great Cairn Hut is a remote bivy shelter most commonly used by climbers who access the region via helicopter—but it works just as well for harebrained run-ventures.

Right before midnight, 18 hours into our first day, we arrived at a remote climbers’ cabin: our pausing point for the night. By our definition, this was a wild success.

The following day promised heinous bushwhacking down a steep, trailless creek bed. We figured that crux would take four to six hours. Once through, a vague alpine trail system would lead to our eastern egress.

As it turned out, the “creek” we’d identified on the map was actually a roaring glacial river that sliced through numerous box canyons. Over the next eight hours, we clung to thorny devil’s club, waded through seas of stinging nettle, and each managed to get stung by hornets as we navigated irreversible rappels, deadfall tightropes and trampolines of slick alder branches. We inched our way up and down the side of the ravine, logging more vertical mileage than lateral distance downriver.

“Don’t go chasing waterfalls,” they said; nobody ever told us not to climb up them.

By midafternoon, we’d only covered 6 miles and felt like our feet had hardly touched the ground. By 4 p.m., we’d made almost zero forward progress and decided to pull out far short of the full traverse. Still, none of us felt like we’d left anything unfinished. We’d sought neither a fast time nor a first, but simply an experience: to share something immersive, connective and vulnerable. And so we’d deviated and detoured, untethered yet grounded, moving through mountains in the simplest form.

Most mountain ranges get gnarlier the higher you go, but the Selkirks might be just the opposite. Our planned route only got more complex the deeper we travelled into its valleys. After hours of navigating devil’s club, slide alder, deadfall and stinging nettle, Everett commits to the first of multiple mandatory below-tree-line rappels.

Before bailing, we looked back at the way we’d come. Our route across the steep flanks of the river valley was indiscernible from the dense undergrowth, as if the thicket had sealed itself behind us.

The Selkirk backcountry has a high cost of entry (and exit). Eight hours of dense bushwhacking left its mark on Tristan’s legs.

Matthew Tufts is a journalist from rural Vermont who resides in Revelstoke, British Columbia.